by Anna D. Sinaiko, Ph.D., and Meredith B. Rosenthal, Ph.D

Slowing the growth of health care costs is critical to the long-term fiscal stability of the United States and is the direct or indirect focus of most U.S. health policy initiatives today. One tactic for reducing spending is to increase price transparency in health care — to publish the prices that providers charge or those that a patient would pay for medical care — with the aim of lowering prices overall. More than 30 states are considering or pursuing legislation to increase price transparency (see table). Most initiatives focus on publishing average or median within-hospital prices for individual services, though information on total and out-of-pocket costs for episodes of care across different sites are available in some markets (e.g., New Hampshire). At the federal level, three bills designed to increase transparency were introduced in Congress in 2010 and attracted some early bipartisan support. In addition, several commercial health insurance plans release information to their members about the prices charged by hospitals and physicians for common services and procedures.

At one level, it’s the wide variation in medical prices within U.S. markets that creates an opportunity for transparency to reduce spending. This variation exists even for relatively common procedures. In New Hampshire in 2008, the average payment for arthroscopic knee surgery was $2,406 with a standard deviation of $1,203 in hospital settings and $2,120 with a standard deviation of $1,358 in nonhospital settings.1 In Massachusetts, the median hospital cost in 2006 and 2007 for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine, performed without contrast material, ranged from $450 to $1,675.2

Since consumers are generally ignorant of such price differences, publishing price information could both narrow the range and lower the level of prices, in part by permitting consumers to engage in more cost-conscious shopping and select lower-cost providers and in part by stimulating price competition on the supply side, forcing high-priced providers to lower their prices (or accept smaller annual increases) in order to remain competitive. Proponents argue that consumers have price information and compare costs when purchasing just about any other good (imagine buying a car, a house, or a computer without knowing its price) and that health care should be no different.

Health care does differ from other consumer goods in a few important ways, however, that are likely to affect patients’ responses to price information.

More

This blog tracks aging and disability news. Legislative information is provided via GovTrack.us.

In the right sidebar and at the page bottom, bills in the categories of Aging, Disability, Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security are tracked.

Clicking on the bill title will connect to GovTrack updated bill status.

Showing posts with label Costs. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Costs. Show all posts

Friday, March 11, 2011

Sunday, January 2, 2011

Putting the Value Framework to Work | Health Policy and Reform

by Thomas H. Lee, M.D.

“Value” is a word that has long aroused skepticism among physicians, who suspect it of being code for “cost reduction.” Nevertheless, an increasing number of health care delivery organizations, including my own, now describe enhancement of value for patients as a fundamental goal and are using concepts developed by Michael Porter (see 10.1056/NEJMp1011024, and the framework papers in Supplementary Appendixes 1 and 2 of that article) to shape their strategies. What has changed? And what are these organizations actually doing?

Practical motivations lie behind the interest in the value framework. Rising costs and a stagnant economy pose problems with no easy solution. Budgets cannot be planned responsibly by hoping for growth in volume. As all players try to protect their incomes, nerves are fraying. Physicians are pitted against hospitals, specialists against primary care physicians, academics against the community.

In this fractious context, value is emerging as a concept — perhaps the only concept — that all stakeholders in health care embrace.

Full Article

“Value” is a word that has long aroused skepticism among physicians, who suspect it of being code for “cost reduction.” Nevertheless, an increasing number of health care delivery organizations, including my own, now describe enhancement of value for patients as a fundamental goal and are using concepts developed by Michael Porter (see 10.1056/NEJMp1011024, and the framework papers in Supplementary Appendixes 1 and 2 of that article) to shape their strategies. What has changed? And what are these organizations actually doing?

Practical motivations lie behind the interest in the value framework. Rising costs and a stagnant economy pose problems with no easy solution. Budgets cannot be planned responsibly by hoping for growth in volume. As all players try to protect their incomes, nerves are fraying. Physicians are pitted against hospitals, specialists against primary care physicians, academics against the community.

In this fractious context, value is emerging as a concept — perhaps the only concept — that all stakeholders in health care embrace.

Full Article

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

U.S. GAO - Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drugs: Estimated Changes to Federal Upper Limits Using the Formula under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

GAO-11-141R December 15, 2010 Full Report (PDF, 15 pages)

Spending on prescription drugs in Medicaid--the joint federal-state program that finances medical services for certain low-income adults and children--totaled $15.2 billion in fiscal year 2008. State Medicaid programs do not directly purchase prescription drugs; instead, they reimburse retail pharmacies for covered prescription drugs dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries. The federal government provides matching funds to state Medicaid programs to help cover a portion of the cost of these reimbursements. For certain outpatient prescription drugs for which there are three or more therapeutically equivalent versions, state Medicaid programs may only receive federal matching funds for reimbursements up to a maximum amount, which is known as a federal upper limit (FUL). FULs were designed as a cost-containment strategy and have historically been calculated as 150 percent of the lowest published price for the therapeutically equivalent versions of a given drug from among the prices published nationally in three drug pricing compendia. The prices from these compendia are list prices suggested by drug manufacturers and do not reflect actual transaction prices. State Medicaid programs have the authority to determine their own reimbursement amounts to retail pharmacies for covered prescription drugs. However, for drugs subject to a FUL, the federal government will only provide matching funds to the extent that a state's annual reimbursements do not exceed the sum of the FULs for all such drugs. Concerns have been raised about FULs calculated based on compendia prices. For example, a 2005 report by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that FULs calculated in this manner were ineffective at controlling spending on these drugs. The 2005 OIG report found that the prices in the three price compendia used to set FULs often greatly exceeded prices in the marketplace. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) established a FUL formula based on average manufacturer price (AMP) rather than compendia prices. In contrast to compendia prices, AMP represents the average of actual transaction prices paid to manufacturers for a given drug and is typically less than any of a drug's published compendium prices. Drug manufacturers are required to report AMPs to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on a monthly basis. DRA also expanded the list of drugs subject to a FUL from those with three or more therapeutically equivalent versions to include drugs with two or more therapeutically equivalent versions. Congressional interest in controlling prescription drug costs using AMP-based FULs continues. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) established a new AMP-based formula for calculating FULs and changed the definition of AMP.8 Under PPACA, FULs are to be calculated as no less than 175 percent of the utilization-weighted average of the most recently reported monthly AMPs for the pharmaceutically and therapeutically equivalent versions of a drug. Congress expressed interest in an early indication of the potential effects of PPACA on FULs and asked us to examine the likely effects of PPACA's AMP-based formula by drawing upon data from 2008 that we gathered for our November 2009 report, including 2008 AMPs that pre-date PPACA's changes to the definition of AMP. This report examines how, for selected drugs, estimated FULs using PPACA's AMP-based formula and 2008 data compare to pre-PPACA FULs and to average retail pharmacy acquisition costs.

We found that for most of the drugs in our sample, using AMP and other data from 2008, FULs based on PPACA's formula were lower than pre-PPACA FULs and higher than average retail pharmacy acquisition costs.

Full Summary

Spending on prescription drugs in Medicaid--the joint federal-state program that finances medical services for certain low-income adults and children--totaled $15.2 billion in fiscal year 2008. State Medicaid programs do not directly purchase prescription drugs; instead, they reimburse retail pharmacies for covered prescription drugs dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries. The federal government provides matching funds to state Medicaid programs to help cover a portion of the cost of these reimbursements. For certain outpatient prescription drugs for which there are three or more therapeutically equivalent versions, state Medicaid programs may only receive federal matching funds for reimbursements up to a maximum amount, which is known as a federal upper limit (FUL). FULs were designed as a cost-containment strategy and have historically been calculated as 150 percent of the lowest published price for the therapeutically equivalent versions of a given drug from among the prices published nationally in three drug pricing compendia. The prices from these compendia are list prices suggested by drug manufacturers and do not reflect actual transaction prices. State Medicaid programs have the authority to determine their own reimbursement amounts to retail pharmacies for covered prescription drugs. However, for drugs subject to a FUL, the federal government will only provide matching funds to the extent that a state's annual reimbursements do not exceed the sum of the FULs for all such drugs. Concerns have been raised about FULs calculated based on compendia prices. For example, a 2005 report by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that FULs calculated in this manner were ineffective at controlling spending on these drugs. The 2005 OIG report found that the prices in the three price compendia used to set FULs often greatly exceeded prices in the marketplace. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) established a FUL formula based on average manufacturer price (AMP) rather than compendia prices. In contrast to compendia prices, AMP represents the average of actual transaction prices paid to manufacturers for a given drug and is typically less than any of a drug's published compendium prices. Drug manufacturers are required to report AMPs to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on a monthly basis. DRA also expanded the list of drugs subject to a FUL from those with three or more therapeutically equivalent versions to include drugs with two or more therapeutically equivalent versions. Congressional interest in controlling prescription drug costs using AMP-based FULs continues. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) established a new AMP-based formula for calculating FULs and changed the definition of AMP.8 Under PPACA, FULs are to be calculated as no less than 175 percent of the utilization-weighted average of the most recently reported monthly AMPs for the pharmaceutically and therapeutically equivalent versions of a drug. Congress expressed interest in an early indication of the potential effects of PPACA on FULs and asked us to examine the likely effects of PPACA's AMP-based formula by drawing upon data from 2008 that we gathered for our November 2009 report, including 2008 AMPs that pre-date PPACA's changes to the definition of AMP. This report examines how, for selected drugs, estimated FULs using PPACA's AMP-based formula and 2008 data compare to pre-PPACA FULs and to average retail pharmacy acquisition costs.

We found that for most of the drugs in our sample, using AMP and other data from 2008, FULs based on PPACA's formula were lower than pre-PPACA FULs and higher than average retail pharmacy acquisition costs.

Full Summary

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Coherent and Transparent Health Care Payment - The Commonwealth Fund

By Karen Davis

The market for health care is not like markets for other goods and services. Information on prices is not typically available, decisions about where to get life-saving care are often made in an emergency, and patients lack knowledge about the value of diagnostic and treatment services and the comparative effectiveness of alternative therapies, or where to go for the best care with the best prospects for full recovery, functioning, and quality of life.

However, there are ways we can improve the functioning of the health care market and increase the value of what we pay for care. The Affordable Care Act includes important provisions to increase access to information on the quality of physician and hospital care and establish multi-payer databases that will provide a more comprehensive picture of patterns of care across providers. It also begins to address the imbalance between primary and specialty care by increasing primary care payment rates under Medicare and Medicaid.

Continue Reading

The market for health care is not like markets for other goods and services. Information on prices is not typically available, decisions about where to get life-saving care are often made in an emergency, and patients lack knowledge about the value of diagnostic and treatment services and the comparative effectiveness of alternative therapies, or where to go for the best care with the best prospects for full recovery, functioning, and quality of life.

However, there are ways we can improve the functioning of the health care market and increase the value of what we pay for care. The Affordable Care Act includes important provisions to increase access to information on the quality of physician and hospital care and establish multi-payer databases that will provide a more comprehensive picture of patterns of care across providers. It also begins to address the imbalance between primary and specialty care by increasing primary care payment rates under Medicare and Medicaid.

Continue Reading

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

The Paying for Eldercare Puzzle

By Alex Guerrero

When thinking about paying for eldercare, it can be overwhelming to consider the many different financial and care options.Differing eligibility requirements and different types of benefits can further the confusion. By grouping options into categories, we can help families better understand programs available to them.

Short Term Resources

Long term elder care often begins by using short term resources. Medicare, Medigap, private health insurance and similar programs for military retirees and veterans such as TRICARE and CHAMPVA all provide limited time benefits for long term care. These programs’ benefits are designed for seniors recovering from surgeries or accidents and are not meant as a long term care solution. However, they will pay a high percentage of the cost of nursing home care for up to 100 days.

Long Term Resources

Resources for ongoing elder care costs can be grouped into 5 categories.

Pensions and Retirement Resources

The first resources most families tap for the cost of eldercare are recurring pensions and retirement savings. These include social security benefits and veteran’s pensions such as the Aid and Attendance benefit and a family’s own savings. The costs and types of long term care have changed dramatically in recent years and unfortunately many of those who require care today did not retire with the recurring monthly income to cover those costs.

Home Equity

With inadequate recurring monthly income to pay for long term care, many families use the equity of their homes as a financial resource. Reverse mortgages and to a lesser extent home equity loans can provide a significant amount of monthly income. There are several new financial programs that allow seniors to tap their home equity as an alternative to reverse mortgages. However, these are only available in some states and their value is somewhat diminished due to the drop in home prices in recent years.

Insurance: Long Term Care and Life

Most families do not have long term care insurance, but those that do receive direct payments to help them with the cost of care. Life insurance is more common and there are multiple options for exchanging a policy for cash. For seniors in poor health, viatical settlements and accelerated death benefits allow them to receive a lump sum payout. Life settlements and death benefits loans are two other options for seniors with life insurance that require care but are not terminally ill.

Programs for the Financially Challenged

There are a variety of programs provided by federal, state and non-profits organizations for the financially needy. Chief among them is Medicaid in its various forms. Qualified seniors can receive Medicaid benefits in various ways; direct care, waivers to receive home care, and family caregivers can even receive payment for the care they provide. Supplemental Security Income can provide a boost to Social Security checks. Some cities offer government housing with assisted living services.

Eldercare Loans

In the last few years, there has emerged a new class of loan specifically targeted at helping families pay for assisted living. The loans have rapid approval processes and are structured to allow multiple family member or friends to share the cost of paying for an elderly individual’s care. These are a good option for families in shorter term, crisis situations.

Reducing the Cost of Care

Another way to think about paying for long term care is to think about how one might reduce the cost of care. This is especially valid for families that care for their loved ones at home. Some respite care programs offered by non-profits and Area Agencies on Aging offer as much as 30 hours / month of care for free or for very reasonable fees. This can offset the need for full-time home care services. There are also federal and state tax credits and deductions for caregivers. The cost of medications can be reduced by purchasing prescriptions online in bulk or from Canadian pharmacies. By combining many of these ideas, families can reduce their cost of care by hundreds or even thousands of dollars per month.

The website, PayingForSeniorCare.com, offers a deeper investigation of the Pros and Cons of each of these financial and care resources. Their Eldercare Financial Resource Locator Tool helps families find which options are relevant to them to help pay for home care, assisted living and long term care. Alex Guerrero serves as the Director of Operations for the organization.

When thinking about paying for eldercare, it can be overwhelming to consider the many different financial and care options.Differing eligibility requirements and different types of benefits can further the confusion. By grouping options into categories, we can help families better understand programs available to them.

Short Term Resources

Long term elder care often begins by using short term resources. Medicare, Medigap, private health insurance and similar programs for military retirees and veterans such as TRICARE and CHAMPVA all provide limited time benefits for long term care. These programs’ benefits are designed for seniors recovering from surgeries or accidents and are not meant as a long term care solution. However, they will pay a high percentage of the cost of nursing home care for up to 100 days.

Long Term Resources

Resources for ongoing elder care costs can be grouped into 5 categories.

Pensions and Retirement Resources

The first resources most families tap for the cost of eldercare are recurring pensions and retirement savings. These include social security benefits and veteran’s pensions such as the Aid and Attendance benefit and a family’s own savings. The costs and types of long term care have changed dramatically in recent years and unfortunately many of those who require care today did not retire with the recurring monthly income to cover those costs.

Home Equity

With inadequate recurring monthly income to pay for long term care, many families use the equity of their homes as a financial resource. Reverse mortgages and to a lesser extent home equity loans can provide a significant amount of monthly income. There are several new financial programs that allow seniors to tap their home equity as an alternative to reverse mortgages. However, these are only available in some states and their value is somewhat diminished due to the drop in home prices in recent years.

Insurance: Long Term Care and Life

Most families do not have long term care insurance, but those that do receive direct payments to help them with the cost of care. Life insurance is more common and there are multiple options for exchanging a policy for cash. For seniors in poor health, viatical settlements and accelerated death benefits allow them to receive a lump sum payout. Life settlements and death benefits loans are two other options for seniors with life insurance that require care but are not terminally ill.

Programs for the Financially Challenged

There are a variety of programs provided by federal, state and non-profits organizations for the financially needy. Chief among them is Medicaid in its various forms. Qualified seniors can receive Medicaid benefits in various ways; direct care, waivers to receive home care, and family caregivers can even receive payment for the care they provide. Supplemental Security Income can provide a boost to Social Security checks. Some cities offer government housing with assisted living services.

Eldercare Loans

In the last few years, there has emerged a new class of loan specifically targeted at helping families pay for assisted living. The loans have rapid approval processes and are structured to allow multiple family member or friends to share the cost of paying for an elderly individual’s care. These are a good option for families in shorter term, crisis situations.

Reducing the Cost of Care

Another way to think about paying for long term care is to think about how one might reduce the cost of care. This is especially valid for families that care for their loved ones at home. Some respite care programs offered by non-profits and Area Agencies on Aging offer as much as 30 hours / month of care for free or for very reasonable fees. This can offset the need for full-time home care services. There are also federal and state tax credits and deductions for caregivers. The cost of medications can be reduced by purchasing prescriptions online in bulk or from Canadian pharmacies. By combining many of these ideas, families can reduce their cost of care by hundreds or even thousands of dollars per month.

The website, PayingForSeniorCare.com, offers a deeper investigation of the Pros and Cons of each of these financial and care resources. Their Eldercare Financial Resource Locator Tool helps families find which options are relevant to them to help pay for home care, assisted living and long term care. Alex Guerrero serves as the Director of Operations for the organization.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Health Care Reform and Cost Control | Health Care Reform Center

by Peter R. Orszag, Ph.D., and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D

After nearly a century of failed attempts, comprehensive health care reform was enacted on March 23, 2010, when President Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In attempting to modernize and improve a large part of the health care system, it may be one of the most ambitious and consequential pieces of legislation in U.S. history.

Although the bill has now been signed into law, the debate over its design and intended effects has not abated. As concerns appropriately mount about the nation’s medium- and long-term fiscal situation, critics of the ACA have resurrected doubts about its cost-containment measures and overall fiscal impact. Many commentators have claimed that the bill focuses mostly on coverage and contains little in the way of cost control.

Yet we would argue that even from a purely “green eyeshade” viewpoint, the bill will significantly reduce costs.

. . . .

But these savings will be illusory if we do not reform health care delivery to bring down the long-term growth in costs, and the ACA puts us on the path to doing just that. In fact, it institutes myriad elements that experts have long advocated as the foundation for effective cost control. More important is how the legislation approaches this goal. The ACA does not establish a rigid bureaucratic structure to be changed only episodically through arduous legislative action. Rather, it establishes dynamic and flexible structures that can develop and institute policies that respond in real time to changes in the system in order to improve quality and restrain unnecessary cost growth.

So what are the cost-control elements of the ACA?

Read Full Article

After nearly a century of failed attempts, comprehensive health care reform was enacted on March 23, 2010, when President Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In attempting to modernize and improve a large part of the health care system, it may be one of the most ambitious and consequential pieces of legislation in U.S. history.

Although the bill has now been signed into law, the debate over its design and intended effects has not abated. As concerns appropriately mount about the nation’s medium- and long-term fiscal situation, critics of the ACA have resurrected doubts about its cost-containment measures and overall fiscal impact. Many commentators have claimed that the bill focuses mostly on coverage and contains little in the way of cost control.

Yet we would argue that even from a purely “green eyeshade” viewpoint, the bill will significantly reduce costs.

. . . .

But these savings will be illusory if we do not reform health care delivery to bring down the long-term growth in costs, and the ACA puts us on the path to doing just that. In fact, it institutes myriad elements that experts have long advocated as the foundation for effective cost control. More important is how the legislation approaches this goal. The ACA does not establish a rigid bureaucratic structure to be changed only episodically through arduous legislative action. Rather, it establishes dynamic and flexible structures that can develop and institute policies that respond in real time to changes in the system in order to improve quality and restrain unnecessary cost growth.

So what are the cost-control elements of the ACA?

Read Full Article

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

TIME GOES BY | REFLECTIONS: On Longevity

by Saul Friedman

This began as an essay on longevity, the advances the United States and much of the world have made in increasing life expectancy. Then I came across this piece from The New York Times of October 24, 1880. The story, entitled, Living Too Long, began:

But it’s not my aim to promote access to good health care, but to examine a strange phenomenon. The world has had great success since 1880 in achieving a longer, heathier life for people almost everywhere. Indeed, life expectancy in most of the world has grown by 10 years just since 1960. And yet, too many Americans, politicians and ordinary people seem to fear longevity, and some are questioning whether we’re living too long.

A woman I met years ago who was the subject of my column on the problems of older Americans, had just placed her husband, suffering from Parkinson’s disease, in a nursing home and she didn’t know how to pay for it and continue to keep up her own home and living standards. “Who knew I would live this long?” she said. She was only 70.

A few weeks ago, a reader told me quite candidly that people on Medicare or Social Security were selfish and should forgo these programs, “that will keep you alive for a few more years; better to use the money to send your grandchildren to college.”

That we on Medicare and Social Security’s are living too long and are a drain on the rest of society is not a new idea. Twenty five years ago, the Atlantic Monthly, with the help of an ugly caricature, depicted older Americans as “Greedy Geezers.”

And about that time, then Gov. Richard Lamm of Colorado told a meeting of lawyers that elderly people who are terminally ill “have a duty to die and get out of the way” rather than try to survive by artificial means. People who allowed themselves to die, he said, are like “leaves falling off a tree and forming humus for other plants to grow...Let the other society, our kids, build a reasonable life.” He figured it’s better to be humus than to watch your grandchildren grow up.

In 1996, as a former governor, Lamm was at it again calling for Medicare to be cut tenfold because it was spending too much prolonging lives. And he predicted tht, as the society ages, “we have to learn to run a nation of 50 Floridas.” As we shall see, that sour vision of the future has cropped up more recently.

But the criticism that Medicare spent too much money on the last years of the lives of beneficiaries, along with efforts by Newt Gingrich’s Republican Congress to privatize Medicare and cut its funding, prompted Medicare in 1995 to begin its hospice program.

Medicare paid fully to care for patients whose doctor attested that they had less than six months to live. Patients who volunteered to enter hospice had to agree that they could receive only palliative care – pain killers and bedside help - to make them comfortable. But they were denied curative treatment, including their own routine medicines, even if there was a chance it would prolong their lives.

But the hospice program gave lie to the notion that death is the answer to saving money. Fortunately, as medical advances such as chemotherapy, open heart surgery and more sophisticated diagnostic techniques like the CT-Scan and PET-Scan became available and common, it was no longer as easy as Lamm suggested to call patients terminally ill, or to predict how much longer they had to live.

Few doctors will tell a patient how long he or she has to live for the course of an illness is not predictable for everyone. Cancer patients today may survive into their eighties. And the severely disabled, like Stephen Hawking, may contribute handsomely to the living.

As a result, Medicare now recognizes that the six-month prediction of a doctor, which is still required, may be extended indefinitely under current Medicare rules. Indeed, some patients get well enough to opt out of hospice care. In addition, Medicare dropped its prohibition on curative care and now permits a cancer patient to continue chemotherapy while in hospice.

Nevertheless, Medicare hospice will take over the care of a patient and is there to provide care for the patient (and comfort for the family) at the end of life.

Thus, it has become obvious that there is nothing predictable about aging except that it will end. Everything else is a matter of luck, background, chance, environment, genes and perception. We are not as old as our parents were at our age. And likely they didn’t live to be our age.

You know the cliches: 40 is the new 30; 60 is the new 50; and so on. As the boomers came of age, AARP recognized the changes in the perception and the realities of aging when it lowered its membership eligibility age to 50. In short, longevity is to be celebrated rather than feared.

One of the first writers to call for a celebration of longevity was social historian, Theodore Roszak, who wrote the classic study of the Sixties and coined a new phrase, in The Making of A Counter Culture. In his 1998 book, America the Wise, he called on the nation to celebrate and welcome the wisdom of America’s booming population of older Americans.

Roszak’s 2001 update of America the Wise, entitled The Longevity Revolution, says of longevity, “It is inevitable. It is good.” His optimism is shared by the godfather of the study of aging, Dr. Robert N. Butler, a geriatrician and founder of the New York-based International Longevity Center, a think tank on issues facing older America.

Butler won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1975 book, Why Survive, a pioneering study of what it’s like to grow old in America. His was not an encouraging picture of “old age.” He became the first director of the National Institute on Aging, and has done more than any one to call attention to the potential and problems of longevity. And despite the longevity alarmists, much has changed for the better.

His latest book, in contrast to his first, celebrates the rewards and possibilities of aging in America. Entitled The Longevity Prescription, Butler, who is active in his eighties, begins with a chapter on “Embracing longevity.” He notes that in the beginning of the 19th Century, life expectancy was 35. “In round numbers we can anticipate living ten thousand days longer than our ancestors could a century ago.”

Butler established the first school of geriatric medicine at New York’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, and speaking as a doctor, Butler says,

His advice includes, how to maintain mental vitality; why you should nurture old and new relationships; and how to get effective medical care.

I have interviewed Butler, was a participant at his first Age boom Academy at his longevity center and I know that he and Roszak are ardent defenders of Social Security and Medicare and advocates for single-payer, universal health insurance. To these ends, the new version of Roszak’s book exposes the rich predators who see longevity as “the Gray Peril,” driving America into bankruptcy because of the increasing costs of Medicare and Social Security.

Chief among these attackers of entitlements is former Nixon Commerce Secretary Pete Peterson, a Wall Street billionaire who now runs the right-wing Concord Coalition, which would privatize Social Security and Medicare. Roszak wrote that Peterson, who published a dire warning about the growth of entitlements in The Atlantic in May,1996, believes that they are unsustainable, unprincipled and unfair.

But more striking, said Roszak, Peterson’s warning treated older Americans as “an alien species of obnoxious, geriatric layabouts thronging the sunny shores of Florida.” He too warned that we should be prepared to become a nation of Floridas.

Nevertheless, Peterson’s long crusade has found comfort in, of all places, the Obama administration. Under pressure from conservative Democrats as well as Republicans, Obama created a commission to deal with the rising deficit. And as expected, the deficit hawks are not singling out the cost of wars and the military, but entitlements, including Social Security, which is sustained by payroll taxes and adds nothing to the deficit. And contrary to too much misleading reporting, it remains financially sound for at least another 30 years.

Peterson, who made millions as a hedge fund manager and took advantage of tax breaks, “continues to lecture on the need to cut Social Security and Medicare for retirees who have a tiny fraction of his wealth,” said economist Dean Baker.

Because of the recession and high unemployment, the Social Security system will pay out more in benefits this year and next than it takes in payroll taxes, but that happened in the recession of 1981-2 and in 1983, Ronald Reagan approved a fix that saved Social Security for 75 years.

Thus Baker chastised the Wall Street Journal for saying the Social Security trust fund will show a deficit; the trust fund earns interest on the bonds it sells to the Treasury and will show a surplus of $100 billion this year.

But on the larger issue of entitlement spending, Princeton’s Uwe Reinhardt, the nation’s leading heath economist put the hysteria about the cost of entitlements in perspective. In a lecture for the Woodrow Wilson School in Washington, he noted that outlays for all Social Security programs, though not part of the budget, will remain flat at six percent of the Gross Domestic Product for the next 60 years, while Medicare spending will rise from the current 3.59 percent to 8.74 percent in 2050.

But not to worry, Reinhardt said. By 2050, even at an annual growth rate of 1.5 percent, the GDP per capita will grow from the current $40,0,000 to $78,200.

I don’t think that will happen unless the Republicans, who are calling for the partial privatization of Social Security, get another chance to govern. Then those of us who welcome our own longevity will have reason to be afraid, very afraid.

TIME GOES BY | REFLECTIONS: On Longevity

This began as an essay on longevity, the advances the United States and much of the world have made in increasing life expectancy. Then I came across this piece from The New York Times of October 24, 1880. The story, entitled, Living Too Long, began:

“Generally speaking, one of the last and least of our anxieties is that we may live too long. Throughout youth and maturity, the prospect of longevity is very apt to be pleasant, for the thing itself seems desirable – far more so in the distance than if at hand.”As usual, The Times came to no conclusion although the article made a strong case against growing too old without telling us how long is too long? In 1880, the life expectancy in the U.S. for white males was 40. Today it’s 78.2, somewhat less than Japan (82.6) and most of Europe, (in the 80s) all of which provide universal health care.

But it’s not my aim to promote access to good health care, but to examine a strange phenomenon. The world has had great success since 1880 in achieving a longer, heathier life for people almost everywhere. Indeed, life expectancy in most of the world has grown by 10 years just since 1960. And yet, too many Americans, politicians and ordinary people seem to fear longevity, and some are questioning whether we’re living too long.

A woman I met years ago who was the subject of my column on the problems of older Americans, had just placed her husband, suffering from Parkinson’s disease, in a nursing home and she didn’t know how to pay for it and continue to keep up her own home and living standards. “Who knew I would live this long?” she said. She was only 70.

A few weeks ago, a reader told me quite candidly that people on Medicare or Social Security were selfish and should forgo these programs, “that will keep you alive for a few more years; better to use the money to send your grandchildren to college.”

That we on Medicare and Social Security’s are living too long and are a drain on the rest of society is not a new idea. Twenty five years ago, the Atlantic Monthly, with the help of an ugly caricature, depicted older Americans as “Greedy Geezers.”

And about that time, then Gov. Richard Lamm of Colorado told a meeting of lawyers that elderly people who are terminally ill “have a duty to die and get out of the way” rather than try to survive by artificial means. People who allowed themselves to die, he said, are like “leaves falling off a tree and forming humus for other plants to grow...Let the other society, our kids, build a reasonable life.” He figured it’s better to be humus than to watch your grandchildren grow up.

In 1996, as a former governor, Lamm was at it again calling for Medicare to be cut tenfold because it was spending too much prolonging lives. And he predicted tht, as the society ages, “we have to learn to run a nation of 50 Floridas.” As we shall see, that sour vision of the future has cropped up more recently.

But the criticism that Medicare spent too much money on the last years of the lives of beneficiaries, along with efforts by Newt Gingrich’s Republican Congress to privatize Medicare and cut its funding, prompted Medicare in 1995 to begin its hospice program.

Medicare paid fully to care for patients whose doctor attested that they had less than six months to live. Patients who volunteered to enter hospice had to agree that they could receive only palliative care – pain killers and bedside help - to make them comfortable. But they were denied curative treatment, including their own routine medicines, even if there was a chance it would prolong their lives.

But the hospice program gave lie to the notion that death is the answer to saving money. Fortunately, as medical advances such as chemotherapy, open heart surgery and more sophisticated diagnostic techniques like the CT-Scan and PET-Scan became available and common, it was no longer as easy as Lamm suggested to call patients terminally ill, or to predict how much longer they had to live.

Few doctors will tell a patient how long he or she has to live for the course of an illness is not predictable for everyone. Cancer patients today may survive into their eighties. And the severely disabled, like Stephen Hawking, may contribute handsomely to the living.

As a result, Medicare now recognizes that the six-month prediction of a doctor, which is still required, may be extended indefinitely under current Medicare rules. Indeed, some patients get well enough to opt out of hospice care. In addition, Medicare dropped its prohibition on curative care and now permits a cancer patient to continue chemotherapy while in hospice.

Nevertheless, Medicare hospice will take over the care of a patient and is there to provide care for the patient (and comfort for the family) at the end of life.

Thus, it has become obvious that there is nothing predictable about aging except that it will end. Everything else is a matter of luck, background, chance, environment, genes and perception. We are not as old as our parents were at our age. And likely they didn’t live to be our age.

You know the cliches: 40 is the new 30; 60 is the new 50; and so on. As the boomers came of age, AARP recognized the changes in the perception and the realities of aging when it lowered its membership eligibility age to 50. In short, longevity is to be celebrated rather than feared.

One of the first writers to call for a celebration of longevity was social historian, Theodore Roszak, who wrote the classic study of the Sixties and coined a new phrase, in The Making of A Counter Culture. In his 1998 book, America the Wise, he called on the nation to celebrate and welcome the wisdom of America’s booming population of older Americans.

“The future belongs to maturity,” he wrote. “Never before has an older generation (more than 80 million Americans in their sixties, seventies, eighties and even nineties) been so conversant with so many divergent ideas and dissenting values.”His book was published before the full force of the digital explosion, but the older generation, the aging boomers and even those who may be called elderly, are not lagging behind younger Americans in their skills with computers and accompanying gadgets. Indeed, the geniuses at Apple, Google, IBM, Microsoft and Amazon are beyond their boomer years.

Roszak’s 2001 update of America the Wise, entitled The Longevity Revolution, says of longevity, “It is inevitable. It is good.” His optimism is shared by the godfather of the study of aging, Dr. Robert N. Butler, a geriatrician and founder of the New York-based International Longevity Center, a think tank on issues facing older America.

Butler won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1975 book, Why Survive, a pioneering study of what it’s like to grow old in America. His was not an encouraging picture of “old age.” He became the first director of the National Institute on Aging, and has done more than any one to call attention to the potential and problems of longevity. And despite the longevity alarmists, much has changed for the better.

His latest book, in contrast to his first, celebrates the rewards and possibilities of aging in America. Entitled The Longevity Prescription, Butler, who is active in his eighties, begins with a chapter on “Embracing longevity.” He notes that in the beginning of the 19th Century, life expectancy was 35. “In round numbers we can anticipate living ten thousand days longer than our ancestors could a century ago.”

Butler established the first school of geriatric medicine at New York’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, and speaking as a doctor, Butler says,

“The average American does not need to resign himself or herself to spending these added decades descending slowly and unhappily into disease and disability...You are not your parents’ genes.”And he proceeds to dispel some of the myths of aging and he prescribes some reasonable things all of us can do to prevent illness and remain active and mentally alert. “No matter what your age, there are ways to enhance your longevity.” They seem as obvious as his admonition to quit smoking (Butler was a smoker), but they are too often overlooked.

His advice includes, how to maintain mental vitality; why you should nurture old and new relationships; and how to get effective medical care.

I have interviewed Butler, was a participant at his first Age boom Academy at his longevity center and I know that he and Roszak are ardent defenders of Social Security and Medicare and advocates for single-payer, universal health insurance. To these ends, the new version of Roszak’s book exposes the rich predators who see longevity as “the Gray Peril,” driving America into bankruptcy because of the increasing costs of Medicare and Social Security.

Chief among these attackers of entitlements is former Nixon Commerce Secretary Pete Peterson, a Wall Street billionaire who now runs the right-wing Concord Coalition, which would privatize Social Security and Medicare. Roszak wrote that Peterson, who published a dire warning about the growth of entitlements in The Atlantic in May,1996, believes that they are unsustainable, unprincipled and unfair.

But more striking, said Roszak, Peterson’s warning treated older Americans as “an alien species of obnoxious, geriatric layabouts thronging the sunny shores of Florida.” He too warned that we should be prepared to become a nation of Floridas.

Nevertheless, Peterson’s long crusade has found comfort in, of all places, the Obama administration. Under pressure from conservative Democrats as well as Republicans, Obama created a commission to deal with the rising deficit. And as expected, the deficit hawks are not singling out the cost of wars and the military, but entitlements, including Social Security, which is sustained by payroll taxes and adds nothing to the deficit. And contrary to too much misleading reporting, it remains financially sound for at least another 30 years.

Peterson, who made millions as a hedge fund manager and took advantage of tax breaks, “continues to lecture on the need to cut Social Security and Medicare for retirees who have a tiny fraction of his wealth,” said economist Dean Baker.

Because of the recession and high unemployment, the Social Security system will pay out more in benefits this year and next than it takes in payroll taxes, but that happened in the recession of 1981-2 and in 1983, Ronald Reagan approved a fix that saved Social Security for 75 years.

Thus Baker chastised the Wall Street Journal for saying the Social Security trust fund will show a deficit; the trust fund earns interest on the bonds it sells to the Treasury and will show a surplus of $100 billion this year.

But on the larger issue of entitlement spending, Princeton’s Uwe Reinhardt, the nation’s leading heath economist put the hysteria about the cost of entitlements in perspective. In a lecture for the Woodrow Wilson School in Washington, he noted that outlays for all Social Security programs, though not part of the budget, will remain flat at six percent of the Gross Domestic Product for the next 60 years, while Medicare spending will rise from the current 3.59 percent to 8.74 percent in 2050.

But not to worry, Reinhardt said. By 2050, even at an annual growth rate of 1.5 percent, the GDP per capita will grow from the current $40,0,000 to $78,200.

“Why should I worry about who will be running the world in 2050,” said Reinhardt, “when they will have so much real GDP to play with.”Finally, Pete Peterson and his Wall Street allies are smart enough to know, for example, that Social Security is not a budget problem. So why are they attacking it? For the same reason George W. Bush sought to turn the insurance and pension program into millions of 401(k)s: think of how Wall Street will celebrate if the brokers and bankers can get their hands on the bonds in the trust fund, worth $2.5 trillion.

I don’t think that will happen unless the Republicans, who are calling for the partial privatization of Social Security, get another chance to govern. Then those of us who welcome our own longevity will have reason to be afraid, very afraid.

TIME GOES BY | REFLECTIONS: On Longevity

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Poll: Most Californians Unprepared for Costs of Long-Term Care

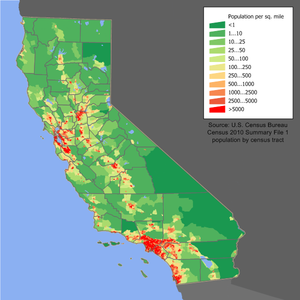

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Fifty-eight percent of registered California voters age 40 and older say they feel unprepared to pay for services if they could no longer care for themselves independently and needed long-term care.

Two-thirds — including majorities across political parties — say they are worried about long-term care costs, as are 75 percent of those who are currently providing help to family or friends and 74 percent those who anticipate providing help in the near future. Concern also spans all income levels, including 63 percent of those reporting annual incomes of $75,000 and above.

The poll, conducted by Lake Research Partners and American Viewpoint, surveyed more than 1,200 registered California voters age 40 and older in English and Spanish about long-term care issues.

The poll sought to better understand long-term care issues facing mid-age and older voters, given that the number of older Californians is projected to nearly double to 8 million in the next 25 years.

Continue Reading

Friday, April 9, 2010

IT Saves $3 Billion in VA Health System from MedPage Today

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

The Department of Veterans Affairs' long-term investment in healthcare information technology paid off at a rate of more than $500 million in net annual benefits from 2001 to 2007, researchers said.

That added up to more than $3 billion in benefits for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) during the study period, after an initial billion-dollar loss.

In particular, the department's computerized patient record system "was the dominant contributor to both benefits and costs in our analysis," wrote Colene M. Byrne, PhD, and colleagues at the Center for Information Technology Leadership in Charlestown, Mass., in the April issue of Health Affairs.

Continue Reading

Related articles by Zemanta

- Study: VA's Computer Systems Cost Billions, but Have Big Payback (blogs.wsj.com)

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Older Adults With Melanoma Incur Significant Costs

(Medical News Today) Treating melanoma in older adults is estimated to cost approximately $249 million annually. Anne M. Seidler, M.D., M.B.A., Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, and colleagues used national databases to assess health care resource consumption by a total of 1,858 patients age 65 and older with melanoma during fiscal years 1991 to 1996.

Melanoma-related charges for older patients totaled an estimated $2,200 per month during the first four months of treatment, close to $4,000 monthly during the last six months and about $900 per month in the interim phase. Per patient, lifetime disease-related costs totaled up to $28,210 from the time of diagnosis to the time of death.

Continue Reading

Melanoma-related charges for older patients totaled an estimated $2,200 per month during the first four months of treatment, close to $4,000 monthly during the last six months and about $900 per month in the interim phase. Per patient, lifetime disease-related costs totaled up to $28,210 from the time of diagnosis to the time of death.

Continue Reading

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Impact on Senior Citizens of Rising Drug Prices in Medicare to Be Hearing Topic

The Special Committee on Aging will convene Wednesday, March 17, for a hearing to examine the rise of prescription drug prices in America and its impact on senior citizens who participate in the Medicare Part D program. Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL) will be the acting chairman.

Witnesses will offer testimony on various topics, including cost-sharing under Part D, how pharmaceutical pricing makes it difficult for Part D plans to negotiate discounts, and policy options for closing the doughnut hole and curbing escalating drug prices, according to a news release from the office of the committee chairman, Sen. Herb Kohl (D-WI).

“Seniors Feeling the Squeeze: Rising Drug Prices and the Part D Program,” will convene at 2:30 p.m. in Room 562, Dirksen Senate Office Building.

Among those providing testimony will be the following.

● Dr. Gerard Anderson, Director, Center for Hospital Finance and Management, and Professor, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD

● John Dicken, Director, Health Care, U.S. Government Accountability Office, Washington, D.C.

● Greg Hamilton, pharmaceutical industry expert, Algonquin, IL

● Willafay McKenna, Medicare Part D beneficiary, Williamsburg, VA

● John Calfee, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C.

The hearing can be viewed live or at a later time by a webcast. A link to the webcast can be found at the committee’s website: http://www.aging.senate.gov/

Witnesses will offer testimony on various topics, including cost-sharing under Part D, how pharmaceutical pricing makes it difficult for Part D plans to negotiate discounts, and policy options for closing the doughnut hole and curbing escalating drug prices, according to a news release from the office of the committee chairman, Sen. Herb Kohl (D-WI).

“Seniors Feeling the Squeeze: Rising Drug Prices and the Part D Program,” will convene at 2:30 p.m. in Room 562, Dirksen Senate Office Building.

Among those providing testimony will be the following.

● Dr. Gerard Anderson, Director, Center for Hospital Finance and Management, and Professor, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD

● John Dicken, Director, Health Care, U.S. Government Accountability Office, Washington, D.C.

● Greg Hamilton, pharmaceutical industry expert, Algonquin, IL

● Willafay McKenna, Medicare Part D beneficiary, Williamsburg, VA

● John Calfee, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C.

The hearing can be viewed live or at a later time by a webcast. A link to the webcast can be found at the committee’s website: http://www.aging.senate.gov/

Monday, March 15, 2010

Economists, Dems Differ On Who's To Blame For Insurers' Rate Hikes - Kaiser Health News

(Kaiser Health News) Democrats assailed health insurers for hiking rates in recent weeks to gain popular momentum for their health overhaul, but health economists say insurers did cause high health costs, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reports. The economists "contend that insurance companies, while often meriting criticism for their practices, aren't to blame for high health care costs." Uwe Reinhardt, a Princeton University economist, said. "What really drives it is the cost trend of health care, which is composed in part of utilization and in part of prices. … In our market-driven system, a doctor or hospital essentially charges the maximum they can get," he added (Boulton, 3/13).

Meanwhile Democrats continue to push the argument that insurers are responsible, The Portsmouth (N.H.) Herald reports. "United States Sen. Jeanne Shaheen said she sees the increases in the health insurance premiums of Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Hampshire as emblematic of a disconnect between health insurance companies and rank-and-file Granite Staters — and all Americans, for that matter." In New Hampshire, hikes ranged from 12 to 13 percent for individual plans and 17 percent for group policies, far less than the biggest 39 percent increases in California (McDermott, 3/14).

Continue Reading

Meanwhile Democrats continue to push the argument that insurers are responsible, The Portsmouth (N.H.) Herald reports. "United States Sen. Jeanne Shaheen said she sees the increases in the health insurance premiums of Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Hampshire as emblematic of a disconnect between health insurance companies and rank-and-file Granite Staters — and all Americans, for that matter." In New Hampshire, hikes ranged from 12 to 13 percent for individual plans and 17 percent for group policies, far less than the biggest 39 percent increases in California (McDermott, 3/14).

Continue Reading

Thursday, March 11, 2010

TIME GOES BY | A Theory of Health Care Spending

by Ronni Bennett

For a good while, I've had a half-baked and only half-joking theory that health care spending would not be so high if we were not constantly reminded of all the things that could be wrong with us.

I watch or listen to television news in short bursts of a few minutes each throughout the day. My general impression is that well over half – perhaps even three-quarters – of commercials are disease related. To see if that is anywhere near true, I grabbed a book yesterday morning and settled down to spend a random hour with television to make notes on the topics of the commercials.

That much time was not needed. I was shocked to find that in the period of one, three-minute commercial break, remedies for the following diseases and conditions were advertised:

COPD

High blood pressure

High cholesterol

Dry skin

Headache

Insomnia

Allergies

Nasal congestion

Foot problems

Heart disease

Constipation

Depression

That's a lot of health problems to cram into three minutes and it is repeated all day on all channels except, possibly, MTV which undoubtedly highlights acne cures.

Continue Reading

For a good while, I've had a half-baked and only half-joking theory that health care spending would not be so high if we were not constantly reminded of all the things that could be wrong with us.

I watch or listen to television news in short bursts of a few minutes each throughout the day. My general impression is that well over half – perhaps even three-quarters – of commercials are disease related. To see if that is anywhere near true, I grabbed a book yesterday morning and settled down to spend a random hour with television to make notes on the topics of the commercials.

That much time was not needed. I was shocked to find that in the period of one, three-minute commercial break, remedies for the following diseases and conditions were advertised:

COPD

High blood pressure

High cholesterol

Dry skin

Headache

Insomnia

Allergies

Nasal congestion

Foot problems

Heart disease

Constipation

Depression

That's a lot of health problems to cram into three minutes and it is repeated all day on all channels except, possibly, MTV which undoubtedly highlights acne cures.

Continue Reading

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Hospital Cost of Care, Quality of Care, and Readmission Rates: Penny-Wise and Pound-Foolish - The Commonwealth Fund

A study of Medicare beneficiaries admitted to U.S. hospitals with congestive heart failure or pneumonia showed no definitive connection between the cost and quality of care, or between cost and death rates.

The Issue

Hospitals face increasing pressure to lower the cost of health care while at the same time improving quality. Some experts are concerned about the trade-offs between the two goals, wondering whether hospitals with lower costs and lower expenditures might devote less effort to improving quality. Critics wonder if the drive to lower costs might create a "penny-wise and pound-foolish" approach, with hospitals discharging patients sooner, only to increase readmission rates and incur greater inpatient use—and costs—over time. To examine the relationships between quality and cost, researchers analyzed discharge, cost, and quality data for Medicare patients with congestive heart failure and pneumonia at more than 3,000 hospitals.

Continue Reading

The Issue

Hospitals face increasing pressure to lower the cost of health care while at the same time improving quality. Some experts are concerned about the trade-offs between the two goals, wondering whether hospitals with lower costs and lower expenditures might devote less effort to improving quality. Critics wonder if the drive to lower costs might create a "penny-wise and pound-foolish" approach, with hospitals discharging patients sooner, only to increase readmission rates and incur greater inpatient use—and costs—over time. To examine the relationships between quality and cost, researchers analyzed discharge, cost, and quality data for Medicare patients with congestive heart failure and pneumonia at more than 3,000 hospitals.

Continue Reading

Monday, February 15, 2010

Individual insurance rates soar in 4 states - washingtonpost.com

By LINDA A. JOHNSON - The Associated Press

Consumers in at least four states who buy their own health insurance are getting hit with premium increases of 15 percent or more - and people in other states could see the same thing.

Continue Reading

Consumers in at least four states who buy their own health insurance are getting hit with premium increases of 15 percent or more - and people in other states could see the same thing.

Continue Reading

Friday, February 5, 2010

NOW! Blog » The perils of doing nothing - 17 cents of every dollar

by Jason Rosenbaum

It's been said often, but given today's news, it deserves to be repeated. We can't do nothing about the health care crisis. We need to fix this problem and fix it now.

Overall spending on health care increased to 17 cents for every dollar spent in America last year, the largest one year increase since the government started keeping this record. For every dollar you make, almost one fifth of it goes to health care costs. And it's not stopping there, if health reform is not finished:

Continue Reading

It's been said often, but given today's news, it deserves to be repeated. We can't do nothing about the health care crisis. We need to fix this problem and fix it now.

Overall spending on health care increased to 17 cents for every dollar spent in America last year, the largest one year increase since the government started keeping this record. For every dollar you make, almost one fifth of it goes to health care costs. And it's not stopping there, if health reform is not finished:

Continue Reading

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Medical News: Rising Costs -- the Real Heartbreak of Psoriasis - in Dermatology, Psoriasis from MedPage Today

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

The heartbreak of psoriasis used to be the disease itself. Now it's the skyrocketing cost of treatment.

From 2000 through 2008, the cost of brand-name drugs increased 66% on average, according to Vivianne Beyer, MD, and Stephen Wolverton, MD, of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis (Beyer is currently at St. Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis).

The cost of several of the drugs "greatly outpaced" both general inflation and the overall increase in cost of prescription medicines, the researchers reported in the January issue of Archives of Dermatology.

Read More

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

The Costs of Failure: Lessons from Nixon, Carter & Clinton Reform Efforts - The Commonwealth Fund

The U.S. Congress is on the threshold of historic change that will usher in a new era in American health care. In the last 50 years, three presidents—Nixon, Carter, and Clinton—have made a serious effort to enact reform and failed. The nation simply can not afford to fail again—too much is at stake for those Americans who fail to get the life-saving care they need and for those who pay the bills of ever-rising cost of health care. History makes clear that failing to act on health reform has serious and far-reaching economic ramifications. An examination of trends in health spending over the past 50 years shows that if health reform measures proposed by previous presidents had been enacted and slowed the growth in spending by as little as 1.0 or 1.5 percentage points annually, spending trends in the U.S. would have been closer to those seen in other major industrialized countries and fewer adverse health consequences and economic burdens would have been borne by American families, businesses, and government.

Continue Reading

Download Full Report

Chart Pack PDF PPT

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Medical News: Plavix Ads Increase Medicaid Costs but Not Usage - in Cardiovascular, Coronary Artery Disease from MedPage Today

By John Gever, Senior Editor, MedPage Today

Medicaid expenditures for clopidogrel (Plavix) soared after direct-to-consumer TV ads for the drug began airing, though not because of any change in prescription trends, researchers said.

Clopidogrel usage by Medicaid recipients stayed on the same upward track as before the ads started, but the drug's unit cost jumped 11.8% (P<0.001) when national TV network advertising starting airing in late 2001, reported Michael R. Law, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, B.C., and colleagues.

The net effect was that Medicaid's per-enrollee expense curve for clopidogrel bent upward at that point, the researchers wrote in the Nov. 23 issue of Archives of Internal Medicine.

From 2002 through 2005, Medicaid spending for clopidogrel accelerated by $40.58 per 1,000 enrollees per quarter (95% CI $22.61 to $58.56), above what would have been expected from the prior trend, Law and colleagues found.

"If drug price increases after direct-to-consumer advertising initiation are common, there are important implications for payers and for policy makers in the U.S. and elsewhere," they wrote.

Continue Reading

Medicaid expenditures for clopidogrel (Plavix) soared after direct-to-consumer TV ads for the drug began airing, though not because of any change in prescription trends, researchers said.

Clopidogrel usage by Medicaid recipients stayed on the same upward track as before the ads started, but the drug's unit cost jumped 11.8% (P<0.001) when national TV network advertising starting airing in late 2001, reported Michael R. Law, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, B.C., and colleagues.

The net effect was that Medicaid's per-enrollee expense curve for clopidogrel bent upward at that point, the researchers wrote in the Nov. 23 issue of Archives of Internal Medicine.

From 2002 through 2005, Medicaid spending for clopidogrel accelerated by $40.58 per 1,000 enrollees per quarter (95% CI $22.61 to $58.56), above what would have been expected from the prior trend, Law and colleagues found.

"If drug price increases after direct-to-consumer advertising initiation are common, there are important implications for payers and for policy makers in the U.S. and elsewhere," they wrote.

Continue Reading

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Ezra Klein - An insurance industry CEO explains why American health care costs so much

by Ezra Klein in the Washington Post

Continue Reading

Download Full Report International Federation of Health Plans 2009 Comparative Price Report Medical and Hospital Fees by Country

On Friday, I sat down with Kaiser Permanente CEO George Halvorson to talk about health-care reform. The conversation was long and ranging and will take a while to transcribe. But before we really got into the weeds, Halvorson handed me an astonishing packet of charts. The material was put together by the International Federation of Health Plans, which is pretty much what it sounds like: an association of insurance plans in different countries. But it showed something I've never seen before, at least not at this level of detail: prices.

Continue Reading

Download Full Report International Federation of Health Plans 2009 Comparative Price Report Medical and Hospital Fees by Country

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=7e7dd332-a2a2-4758-aa76-5a442e9e1c9c)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=79d7ba9f-905a-40e1-9c95-b27f88a13fef)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=9a6c0ed0-e7a5-467e-bb2a-80a6ba6e89c0)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=ee14a4be-bb14-4df0-9b6d-74a1c84198bc)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=dfdb6fac-bdea-48d8-af18-209f144fae61)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=24d25927-7acf-47df-a7ef-ac0369df3ccb)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=d4ddb6fb-638e-40a7-a149-49d0bb0baba5)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=d9500bf7-5292-49f3-993e-9928e01fe4c8)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=f32d658f-48cd-4465-a526-3e4da3b28260)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=4a8e49d6-95e2-42e1-999e-b5d658054d03)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=9b9f7df6-5c89-4d05-96c8-40d388c09a87)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_b.png?x-id=308fcaec-04e9-46e7-ae6b-37a23c55c170)